What are popliteal aneurysms?

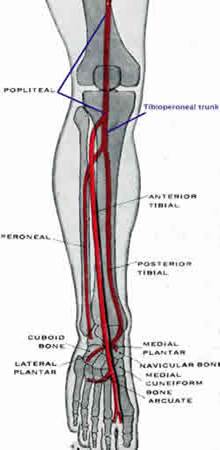

An aneurysm is a swelling of an artery. A popliteal aneurysm is a swelling of the popliteal artery. The popliteal artery extends across the lower third of the thigh and the upper third of the calf. It is situated quite deeply in the leg behind the knee. The popliteal artery is a continuation of the superficial femoral artery in the thigh and below the knee divides into the anterior tibial artery and tibioperoneal trunk which further divides into the posterior tibial and peroneal arteries. The anterior tibial, posterior tibial and peroneal arteries supply arterial blood to the calf and foot. The normal popliteal artery is about 1-1.5 cms wide.

How common are popliteal aneurysms?

It is not clear how frequent these aneurysms are in the general population, but they are relatively uncommon. In a Swedish report they only made up 0.65% of all vascular surgical procedures (about 1 in every 150 procedures). Popliteal aneurysms occur in up to 10% (10 in 100) patients with an aortic aneurysm. Bilateral popliteal aneurysms occur in about 40-50% of patients and about 40-50% of patients will have an associated aortic aneurysm. Popliteal aneurysms are commonly associated with other peripheral aneurysms such as femoral and iliac aneurysms. Most patients (95%) are elderly men with a median age of about 71 years.

Why do popliteal aneurysms develop?

We do not know exactly why popliteal aneurysms develop but they are thought to be caused by atherosclerosis. There are likely to be similarities with aortic aneurysms. In some way the wall of the popliteal artery is weakened probably because of some inherited factors. Atherosclerosis is an important factor but why this might cause dilating disease (aneurysms) in some circumstances and occlusive disease in others is unclear. In patients with multiple aneurysms in different arteries there must be an underlying weakness in the tissues. The exact nature of this has not been clarified yet. Possibly the propensity of the popliteal artery to develop aneurysms is related to the flexion stresses on the artery when the knee is bent and straightened, in conjunction with an underlying tendency for aneurysm development.

Why are popliteal aneurysms important?

The main risk from a popliteal aneurysm is related to embolisation and occlusion (thrombosis) both of which can cause acute leg ischaemia (sudden loss of blood supply to the lower leg). As popliteal aneurysms increase in size they gradually become lined by old blood clot (thrombus). As long as this clot remains attached to the aneurysm there is no danger. If a fragment of blood clot breaks away from the aneurysm, then it can be propelled by the blood flow into smaller arteries downstream in the calf or foot. This process is called embolisation and the fragments of clot will become jammed in the arteries obstructing blood flow to the tissues downstream. As long as this only causes minor damage to the tissues the process can be stopped by treating the aneurysm. The risk of developing complications from a popliteal aneurysm is possibly 30-50% over 3-5 years, but this will depend on the size of the aneurysm.

Popliteal aneurysms can burst (rupture) but this is a much less common complication than embolisation. This is the opposite of aortic aneurysms where the main risk is of the aneurysm bursting and embolisation is much less common (only about 5% of patients).

Popliteal aneurysms can also indicate that the patient is at risk of other aneurysms. Many patients will have a popliteal aneurysm in the opposite leg, an aortic aneurysm or another less common peripheral aneurysm.

If popliteal aneurysms become particularly large then they can also cause compression of neighbouring structures such as nerves and veins. In some cases this can lead to deep venous thrombosis.

Ultimately all these problems can lead to amputation of the leg. In the Swedish study the risk of amputation was greater in in patients with popliteal aneurysms causing symptoms, in situations where the arteries downstream had been damaged by embolisation, those requiring urgent treatment, patients over 70 years and those repaired with a prosthetic graft.

What happens if my popliteal aneurysm blocks or bursts?

Sometimes popliteal aneurysms can suddenly block off and obstruct blood flow to the lower leg and foot. In some patients this will happen and the leg will remain alive and viable. The only symptom these patients notice is pain in the calf muscles on walking (intermittent claudication).

On other occasions this acute blockage can cause severe ischaemia (shortage of blood) resulting in a threatened limb which if not successfully treated within 6-12 hours will require amputation. In these patients there is usually severe pain in the leg associated with tingling or numbness, poor movements or paralysis and pallor or paleness of the leg.

Popliteal aneurysms only very rarely rupture (unlike aortic aneurysms). If they do rupture this will be accompanied by the development of severe pain and a very rapidly enlarging pulsatile lump in the leg.

How do popliteal aneurysms present?

They may be asymptomatic or symptomatic. Asymptomatic aneurysms are discovered when the area behind the knee is examined or the patient undergoes a scan of this area and an enlarged pulsatile artery is found. Approximately 45% of popliteal aneurysms are asymptomatic. Symptomatic popliteal aneurysms may present acutely (as an emergency) or electively at a planned outpatient appointment. Symptomatic aneurysms may present with symptoms due to shortage of blood to the leg, such as claudication, but the patient and referring doctor may be unaware that they are related to a popliteal aneurysm. Once a popliteal aneurysm has blocked, if the patient has only mild symptoms, it is not absolutely necessary to undergo specific treatment for the aneurysm.

What investigations should be performed for a popliteal aneurysm?

The most important investigation for a popliteal aneurysm is an ultrasound scan. This confirms that an aneurysm is present and at the same time can determine the size of the aneurysm. Before treating a popliteal aneurysm most surgeons would also want to have the information that can be obtained from an angiogram. This will provide a road map of the arteries so that a bypass operation may be planned. An angiogram is usually not useful in assessing the size of a popliteal aneurysm as it can only assess the inside of the aneurysm and not the outer wall. The video on the left shows a CT angiogram imaging of popliteal aneurysms.

What are the treatments for popliteal aneurysms?

There are no randomised trials on the treatment of popliteal aneurysms which could guide treatment. Most published experience is based on retrospective reviews of series of patients that have been treated by many different surgeons over a number of years.

Symptomatic aneurysms that have not occluded should always be treated as there is a high risk of amputation without treatment. Symptomatic aneurysms where the popliteal aneurysm has occluded may be treated but the desirability of this will depend on a number of factors which include the degree of patient disability and the complexity of the treatment required.

Some authorities also consider that all asymptomatic popliteal aneurysms should be treated because of the risk of complications. Other experts argue that popliteal aneurysms less than 2 cms can be safely monitored. Most experts advise repair of popliteal aneurysms greater than 3cm (30mm) in diameter. It is possibly more likely your popliteal aneurysm may need treatment if you have had a similar aneurysm treated on the other leg, if you have had an aneurysm treated elsewhere in the body and if you don’t have diabetes (Magee et al 2010). There is some debate on the treatment of popliteal aneurysms between 2 and 3cms and as always the desire to treat in these circumstances must always take into account the general health and age of the patient and the complexity of the intervention.

The chances of success when treating an aneurysm will be strongly influenced by how much of the arterial tree downstream is open with blood flowing and how much is obstructed by old clot.

Surgery

Surgical treatments aim to exclude the aneurysm from the circulation by tying off (ligating) the artery above and below the aneurysm. If this is the only treatment there is a high risk of amputation as although embolisation and rupture will be prevented, the blood flow to the lower leg is obstructed. To avoid this problem a bypass operation is also performed to take blood from the artery above the point of ligation to the artery below the point of ligation (exclusion bypass). This is an above knee to below knee bypass. There are two main approaches to this operation either from behind the knee (less common, posterior approach) or along the inside of the leg (more common, medial approach).

Thrombolysis

Thrombolysis is a technique can be used to clear the arteries downstream from the aneurysm if they become blocked by blood clot when an aneurysm blocks off acutely. It is also used to reopen a blocked aneurysm. It doesn’t treat the aneurysm but clears the arteries in preparation for definitive treatment of the aneurysm. It is only useful when the blood clot is relatively fresh. As the clot becomes older it changes to a harder form which is much more difficult to dissolve

Endovascular techniques

This involves placing a stent graft through the popliteal artery aneurysm. There needs to be a landing zone of more normal artery above and below the aneurysm for the stent graft to remain anchored and blood will travel along the graft to the calf and foot. This excludes all of the blood clot from the circulation. This can be suitable for many aneurysms but is a relatively new technique. The main risks are associated with kinking of the graft from bending the knee which can fracture the metal stents and dislodge the graft or cause it to collapse

Ligation

This means tying off the artery. It will prevent the artery bursting and further embolisation, but there is a high risk of amputation because the blood supply to the lower leg has been interrupted and is no longer used in isolation. It was first described by Antyllus in 200 BC.

Links

http://ageing.oxfordjournals.org/content/28/1/5.full.pdf

http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/12976/54250/54250.pdf

References

Ravn H, Bergqvist D, Bjorck M on behalf of the Swedish Vascular Registry. Nationwide study of the outcome of popliteal artery aneurysms treated surgically. Brit J Surg 2007; 94: 970-977.

Magee R, Quigley F, McCann M, Buttner P, Golledge J. Growth and risk factors for expansion of dilated popliteal arteries. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2010; 39(5): 606-611.